Thursday 23 June.

‘How good is that?’ says Danny, the pleasure evident on his face.

He’s commenting on the fact that Kieran’s eyes are open: a new development since he was here last month. It’s clear that Kieran would be tall standing up. His long, skinny body fills the hospital bed, all elbows and knees. His limbs look very soft, almost boneless, supported here by a complex array of white pillows and bolsters. Both his hands are splinted and his feet are encased in stiff-looking blue foam supports. I assume these are to limit the impact of spasticity – to prevent the tendons and muscles shortening while he lies here. Becky, his mother, sits next to the bed, both hands stroking his forearm while she updates Danny on progress.

‘We think he’s sort of looking at things,’ she says. One of Kieran’s blue eyes – the right one

– is partially occluded by a droopy eyelid. The left one is quite clear. He rolls his head softly. His gaze seems unfocused, hard to read.

We’re in the neurosurgery department of one of London’s largest hospitals, where Danny has been employed for several months as a peer support worker in an early intervention project set up by Headway. It’s the first paid employment he’s had since his injury nearly twenty years ago.

The notes say Kieran has been here two and a half months. He has his own room – partly because of the length of stay, I assume, but also because he’s only seventeen and his parents need to be with him much of the time.

Becky explains that she’s been here seventy-three days straight, alternating ten-hour shifts with her husband, Pete. They don’t leave Kieran alone even at night. For a while they were commuting in but that was unsustainable. The hospital has found them a place to stay on‑site now, thank goodness. Kieran is intubated at the base of his throat, via a tracheotomy. There’s a feeding tube running to his abdomen. A large depression takes up much of the right side of his head, where the skull bone has been removed. The hair and skin make a shadow here where they sink into the cavity.

‘The bone was too smashed up,’ says Becky, ‘so they threw it away. They’ve made a plate to put in instead.’ She shows us a photograph on her phone. It’s of a replica of the missing bone in blue plastic that the hospital has somehow created.

‘Once the plate’s in,’ she continues, ‘once his brain has more space, we might see a bit more improvement, they said. We might,’ she repeats, ‘we don’t know.’ She falls silent as she looks at her son. He rolls his head once more a little.

‘It’ll come gradually,’ says Danny.

‘They said it was a 1 per cent chance of him surviving when they operated,’ she explains. ‘So you just don’t know what will happen.’

‘You’re doing amazing,’ says Danny.

‘Well,’ she says, shrugging, ‘you’ve got to.’

She tells us about the day of the accident. Kieran and his younger brother were messing about on a motorcycle somewhere not far from home. She didn’t know what they were up to. ‘I saw the red helicopter fly over the conservatory,’ she says. ‘I thought, “Something exciting’s happening!” Minutes later his mate was banging on the door: “Come quick! Come quick!” I said, “Is it serious?” and he just burst into tears.’

She explains that the younger brother had his knee smashed. Otherwise he’s fine. Kieran came off worse.

Danny asks when Kieran was born. ‘1998,’ Becky says.

‘There you go,’ says Danny. ‘That was the year I had my injury. We were meant to meet.’ He smiles at Kieran: ‘It’s a privilege.’

Becky asks if Danny is on Facebook. He moves around the bed and looks at her phone, helps her find his profile. He shows her some pictures of his son, Harry, tells her about something they did recently for his first birthday, called ‘cake smash’. ‘It’s a gimmick,’ he says.

‘They give you this massive cake and the babies can just throw themselves at it.’

Becky laughs. It’s obvious that she likes Danny, that he’s a source of reassurance for her.

There are photos on the wall above the bed, signed pictures of footballers mostly.

‘I don’t know who they are, to be honest,’ says Becky.

‘What team do you support?’ asks Danny.

‘Nobody any more,’ she says. ‘I don’t really care now. I suppose it would be West Ham, still. I like to see them win.’

‘Up the Hammers!’ cries Danny with a smile.

Hi Danny! How fantastic to be a part of this project. What were your first thoughts when Ben asked you to be involved with the book?

I was a little bit nervous because some of the content of what I was talking about was a little bit… But at the same time, I was hoping that it’d give people a better understanding of brain injury, that it can happen to anyone at any given time and it doesn’t matter in your heart who or what you are.

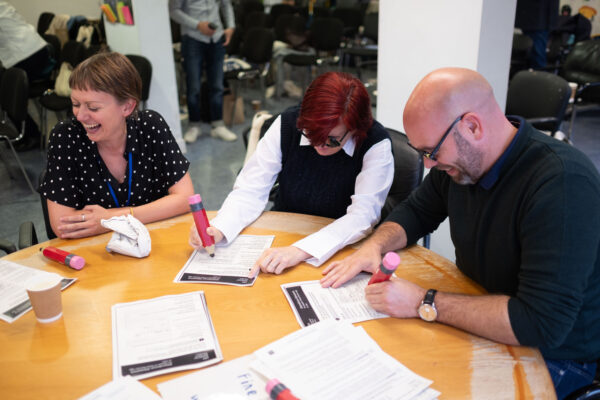

What was the process of writing these stories then, how often did you meet?

We met up once a week for a little while, he came to where I lived, he wanted to get a sense of my surrounding then we’d go for a little walk, so he could understand the area and that and he got to know me more in that time than all the years I’ve known him. He got to know me properly doing this book. He was asking the right questions.

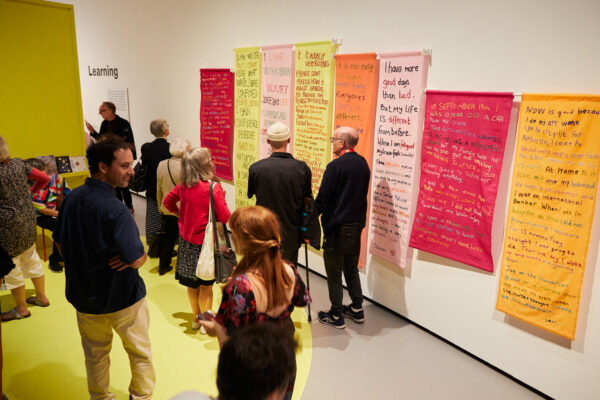

What do you think the benefits are of sharing stories like these with the world, stories of brain injury?

It goes further because it’s not just one isolated story, we’re all completely different people. It highlights that it can happen to anyone and that although we’ve got the same injury, we can have very different symptoms.

In what ways do you think your perspective has changed since your brain injury? The book explores how different your life is now than before your injury.

Definitely. So, I used to take life kind of for granted and I was very arrogant to a degree but now, I’m a lovely geezer. Now I’ve got emotions and I didn’t used to really have that. So, it’s changed me as a person, full circle.

What was it like for you sharing those stories with Ben and now the world? Was it difficult, did it feel cathartic?

It was very emotional and he got me to dig deep in my memory box. Yeah, it was upsetting, because I didn’t realise I was that person before, because I’ve lived with my injury for so long, and to realise I was that person, it hurt me to tell you the truth. I was relieved though, I felt like I was hiding a lot to be honest, so getting it out meant I could feel at ease. You wouldn’t identify me as that person, now, never in a million years because I’m completely different. In a sense as well, it’s rewarding to know how much the injury has made me different as a person.

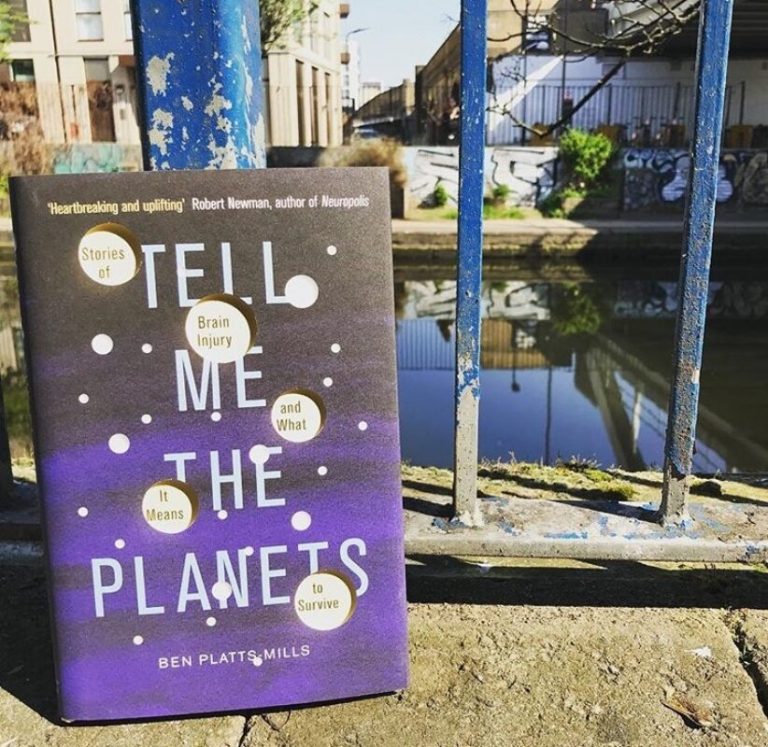

You can buy your copy of Tell Me The Planets on Amazon, and in all good book shops!