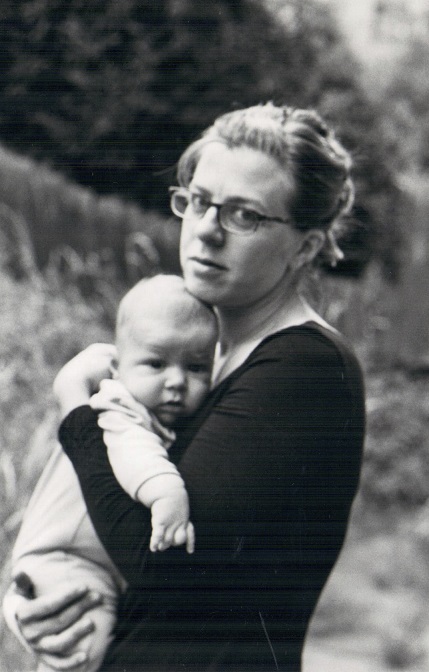

I was thirty years old and I was suddenly the parent. I’ll always remember how Mum looked at me in the early stages – completely without flinching, like a newborn baby.

I was thirty years old and I was suddenly the parent. I’ll always remember how Mum looked at me in the early stages – completely without flinching, like a newborn baby.

To go out, you just need light, preferably. It’s nice to go out in the dark too, although I don’t do it often now.

I think all of us change ways that we function over time. Imagine when you were a little kid; you experience time in a different way, you’re learning so much and so fast. You notice different things as you get older. You think, ‘wow, I’ve come past here hundreds of times but I’ve never noticed that before.’ It might be some feature on a building or a change in season. Look at us now; we’re on the last day of February and the evenings are slowly but definitely getting lighter. There are very lovely signs of bulbs and other plants coming up.

Of course we need to ration our time and use it conveniently but I’m probably not as good at doing that as maybe I ought to be. I’m sure that I vary in the time I use; the time it takes me to do something. Today, when I was slow in making the tea, it was partly because I’d forgotten I was making a pot of tea for you and me to share. Normally to do that, even though I haven’t got an enormous teapot, I would put two teabags in, but I forgot and I put in one bag and when I poured the tea it was a bit weak. It was a perfectly good cup of tea in the end, thank goodness, but it took me longer than I thought.

I often wonder if I am different now from how I would be if I hadn’t had a head injury. I’m not usually brilliantly good at keeping exact time for things and I do feel I can waste many a day. Partly, I have found that to be the case since the head injury, which was twelve years ago now. But I’m not sure I was ever particularly good at managing time.

It can be annoying to other people if you’ve arranged to meet at a certain time and you don’t stick to that. I’ve done that several times with my family: agreed to be down at their place at about midday and then got carried away on something else; you know, that cannot be pleasant for other people.

The way that we get things done in time is important, especially when we’re dealing with children or trying to get something made. There are certain things you shouldn’t miscalculate. One of my jobs, about thirty years ago, was to write a listings section for Time Out magazine and you had to get the copy in by a certain time every week. My deadline was something like 5pm on a Tuesday. One day I didn’t get the things I was meant to be writing in at the right time. The next week Time Out came out without my bit in it and there were a lot of complaints from buyers of the magazine. One shouldn’t be late with work one’s expected to do; so for this life story I hope that I’ll be able to come up with the goods and not be late enough to be left out like I was then! Imagine if it had not been just my listings for a magazine that were late but something more serious.

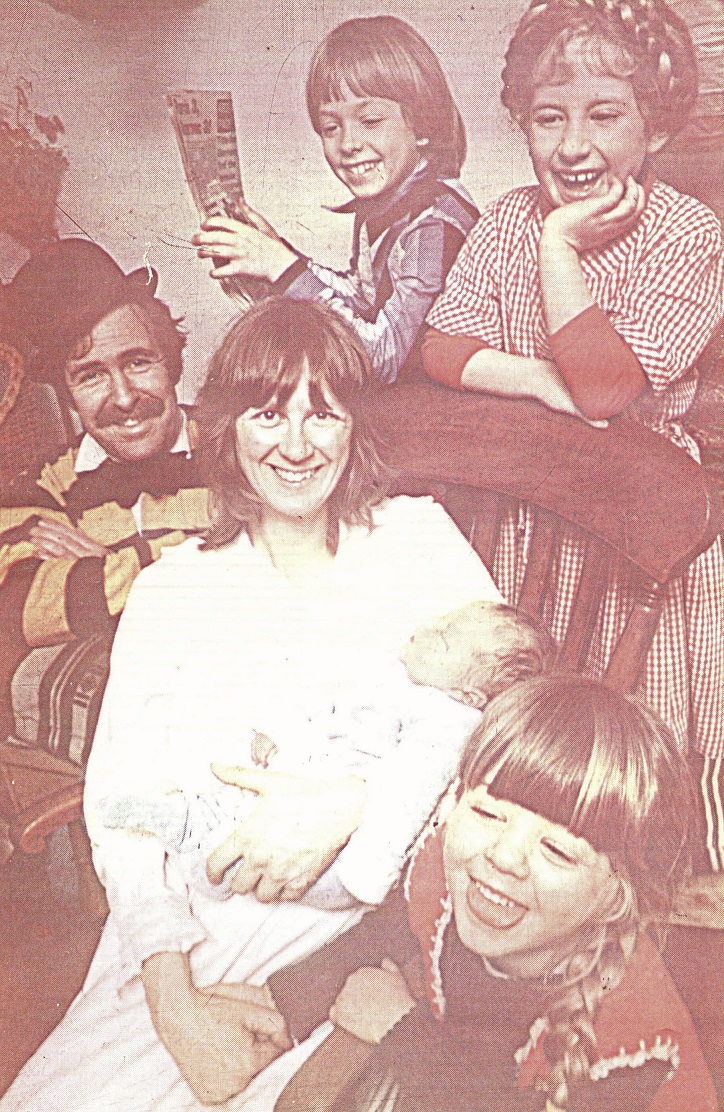

My head injury was in August 2002. I was sixty-three when that happened; I’d just had my birthday. How much more devastating it would have been if it had happened twenty years before. My two sons, Dan and Ben, and two daughters, Leila and Alix, were grown up; if they had been very young it would have been more desperate, for me and them.

When you get an injury like that and you are in hospital for four months, as I was, you’re in other people’s hands. You’re reacting to whatever happened to you; you don’t realise everything that’s happened. So it’s only now that I feel hugely thankful that I was lucky enough to have my offspring and good friends to help and that I was in a good hospital. I realise, looking back at that time, how I managed to get through it and get back on my feet and get back to the sort of things I used to do. Without the help I’ve had, I’d never have done that on my own. I’d be even more different from what I am now and from what I remember.

I had recently qualified into a new job, to be a teacher of English to foreigners. I know that my family had arranged a get together to say goodbye to me for going away to teach with VSO in Rwanda for two years. We had had a party in my former partner Bill’s garden. I don’t have any personal memories of what actually happened on the night of the injury. I’ve seen photos. I realise it did happen, though I don’t remember it. The going away and teaching didn’t happen, after the injury.

I know that the party finished late and I was on my way back to my flat, which was a couple of roads away. I was walking home with a friend, Vlasta, who had come to visit us from Prague. Walking in front of us were my daughter Alix and Miguel, a boyfriend of hers from Portugal. Vlasta has told me that we were just walking along chatting. Suddenly she looked to the left and I wasn’t there. She turned around and I was struggling with my bag, with a man she didn’t know.

He pulled the bag from me and then he must have pushed me quite hard. I fell into some railings along the side of the road, bashed my head hard and was unconscious. The man ran away with my bag. Alix and Miguel turned round and realised I was injured and Alix used her phone to call the ambulance and the police. It just happened one thing after another. Miguel apparently ran after the man who had taken the bag, who went along some paths and then into a flat.

The ambulance and police were not terribly long – it must have been minutes – and the friends must have done what they could. The paramedics took me to the Whittington Hospital. They did some tests on me and said “she’s got a severe head injury and she needs the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery”. So all those arrangements were done without any of my knowledge and I had an operation that night.

My son Dan has told me that a few days later it seemed another operation might be necessary. The family and my friend Sue, who is a doctor, gathered together at the hospital to discuss it. It must have been a difficult situation. Dan asked the neurosurgeon, “would you recommend this for your own mother?” and the surgeon said yes, he would.

I can’t tell you the details because I don’t know them. You’d need to ask the doctors or my family; they would have a clearer picture.

I was walking home with my mum when she was attacked. The whole thing took maybe a minute. She struck her head on the curb and was out cold. She didn’t come round until two weeks later. They first operated that night, to release the internal bleeding that was putting pressure on her brain. A few days later she had a second life-saving operation. They removed part of her left frontal lobe (that was bruised and swelling) and cut a hole in her skull to act like a pressure valve. Her surgeon discussed the consequences with us – that she may lose many higher brain functions. Two that stuck in my mind were losing language or not recognizing her children.

She remained in a coma for a long time. They tested her on the Glasgow coma scale, and she recorded the lowest reaction, a 3 – just distending her limbs, kind of turning out her hands and feet in response to pain. This went on for long enough that the doctors had basically written her off. It’s all probability and precedent. They said no-one with these scores for this long could make a recovery. Phrases like Permanent Vegetative State were used. We were told they had referred her to Putney – that’s the neurological hospital where people who don’t recover go.

We, her children, pleaded with them to let her stay in the acute injuries ward. I think it was a combination of things: believing that she was in there somewhere. Not being ready to confront this future the doctors were painting. Not wanting her to be moved miles away from where we lived. We were coming in every day, taking it in turns to sit with her, talk to her, play music. We asked that she could stay a few more days, just for us to sort ourselves out. We really were pleading. They agreed to three days, I think.

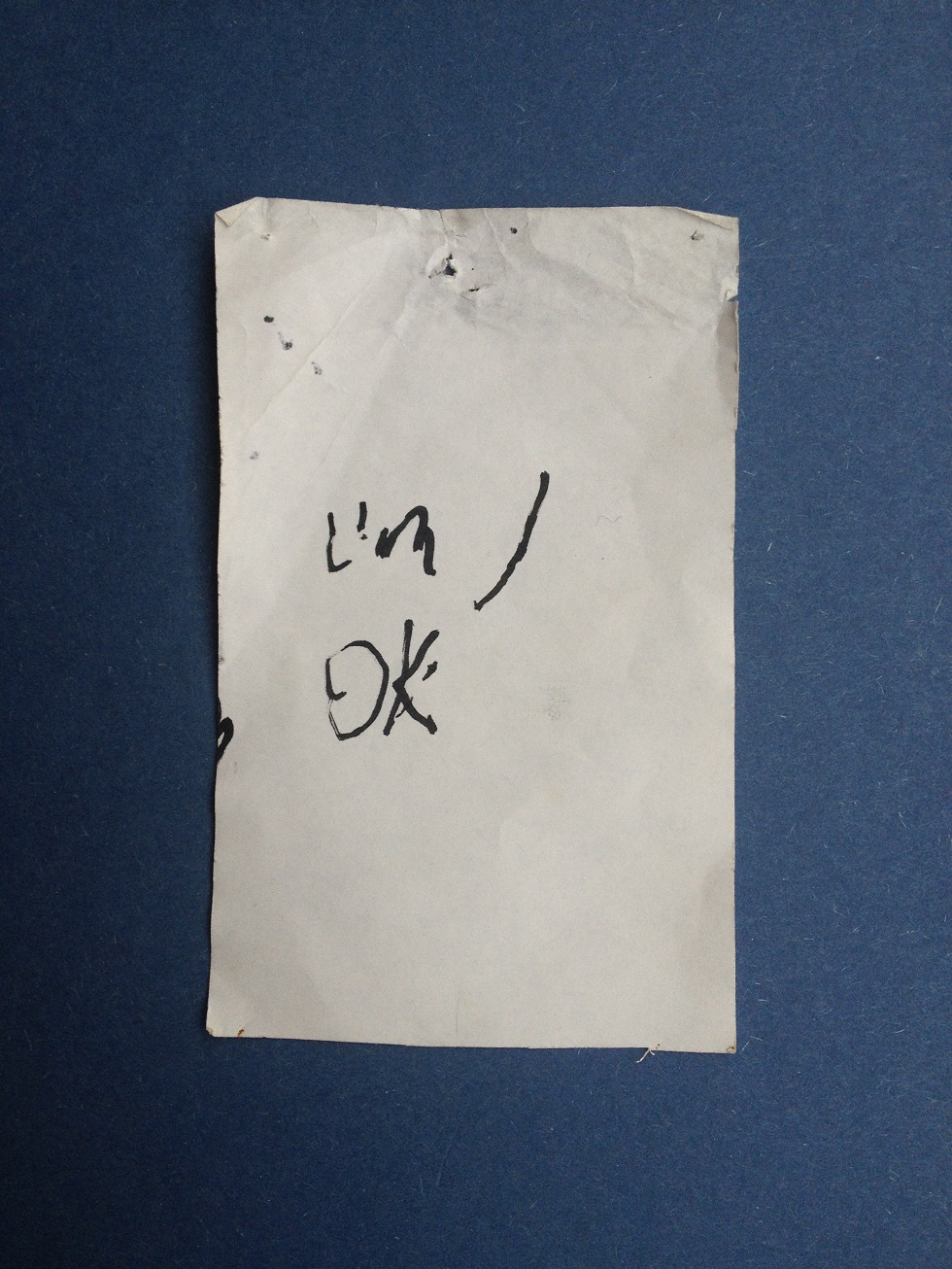

That was when she first moved a finger in her right hand. Soon after, she opened her eyes. I can’t remember the time lag between these events. You lose perspective when you sit and wait for hours on end, when tiny physical movements become so important. Next she moved her hand enough to use a pen. She wrote the note: I’m OK.

That note said so much to us. Firstly, she was just saying she was conscious and alive. Secondly, she had chosen the most concise and efficient way to communicate. This was evidence of a higher faculty at work, to make that rational choice. And thirdly, it was typical of my mother. To be concerned about us, and say something to make us feel better. She wasn’t bloody ok. She was semi-paralysed, couldn’t speak, didn’t know what was going on, but she still wanted to reassure us.

Slowly, over the next four months in that hospital, I began to recover. My huge praise and thanks for their skills – and the skills also of my family and friends – visiting and helping and all those things you need. Only through that help and care can you survive really.

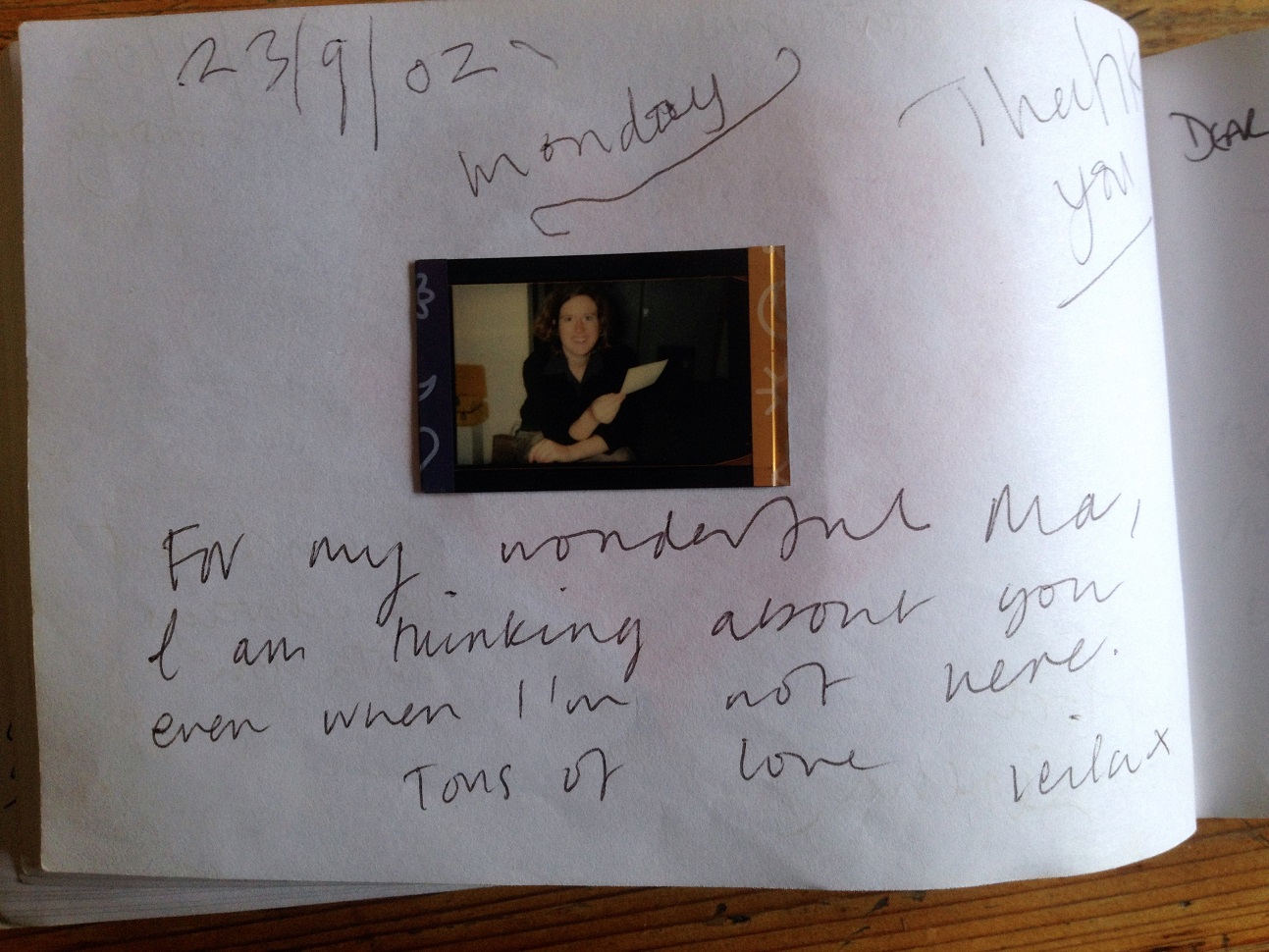

I don’t have memories of the time after the head injury, and I don’t even have clear memories – although I know what was happening in my life – before the head injury. The thing I do have is the visitors’ book my children gave me while I was in hospital, which is a very precious possession because it has helped to put together a picture of what happened. I don’t know whose original thought it was, but what an amazing and important document it is.

In that book there are things that show how I was getting better because there are weird little scribbles I have put in when I realised I could do something. People will write things that they realise you couldn’t do last time they came, and of course I wouldn’t remember the sequence of those without it.

There are messages from close friends, neighbours, work colleagues; people I knew in many different ways. It makes you realise what a difference it makes to go and say hello to someone because we know they’re ill. It does make a difference to your life, however bowled over it is at the time.

All the medical staff treated her case like some miracle. Doctors and nurses came to visit to see for themselves, as if they didn’t believe it. For years after, when we went for outpatient appointments, staff would come and say hello and remark on how extraordinary her recovery was, and tell colleagues who didn’t know: “this is that lady who we thought… the one I told you about.”

They let her stay in the acute injuries ward. She was conscious but had post-traumatic amnesia; her memory lasted about fifteen minutes. She knew who she was, who we were (though she got muddled) but didn’t know where she was or what had happened to her. She’d need it all explained again and again. I remember nurses writing her notes. She’d take the paper to reply, but first she’d correct their spelling and grammar: they would have misspelled ‘subdural haematoma’ so we knew that the fastidious Sarah, the knowledgeable Sarah was in there.

Finally Sarah was assessed and accepted onto the National Hospital’s own rehabilitation unit, which at the time felt like a huge victory, like she’d won a prize. We knew that their unit was amazing, and that she was doing incredibly well if they had accepted her. She was staying in this place that we all knew really well by then.

On 6 December she was released into our care. She still couldn’t walk unaided, feed herself, dress herself, go to the toilet. Someone still had to sleep in a bed next to her for when she woke in the night. I’m one of four children. I did four days a week, and they each did 24 hours. That situation lasted for about eight months. Gradually, slowly, Sarah gained more autonomy. After eight months she could walk unaided, but not go out alone. Someone had to be there through the night, but they could be in another room. After about three years she was living in her new flat alone. Of course with much help and support, but living alone and sleeping though the night without needing help.

Throughout all of this time I don’t remember my mother getting angry, or frustrated, or feeling self-pitiful or bitter or depressed. She had a childlike appetite to re-learn all the necessary things. She laughed a lot. She’d get the giggles that she couldn’t stop, that made all her muscles relax to the point where she might collapse and hurt herself. But it made us laugh too. Her disposition made caring for her so much easier. During our time in intensive care, on the wards, in the rehab unit, we’d seen other patients and their families and we knew how lucky we were.

What are the things we need – the things we could not manage without? We all need somewhere to live, a home, our own space. I grew up in a family with Mum and Dad, four older sisters and two brothers, one older, one younger. We lived in a semi in a town between Bristol and Bath. There were always other people and other things going on. Even if you were doing your own thing, it wasn’t like you were alone, whereas many people grow up with much more of that individual space and time. That’s an interesting way of looking at life, but different. So we need a place. I am realising more as I get older that I don’t want it to be too noisy.

We need food and water. I have a cafe at the bottom of my road and what is so convenient is that you don’t have to keep all the food you need to eat for the whole week in your house. You can take food away or eat there and it doesn’t break the bank although you have to watch what you spend. I do keep food at home, of course, like milk, bread and tea; not loads of food like I used to with the kids.

We need to be able to move and to carry things. I depend on other people for a lift at the moment. Since my head injury I don’t drive a car, but I’m glad I could do when my family was smaller, otherwise we wouldn’t have got to a lot of things that were a great joy to go to. I had a small Volkswagen Beetle which I got when they were quite little – my dad lent me some money to buy it.

I feel I can still move around. I walk a lot. I use buses and trains and tubes. I’m certainly slower at moving now. I can’t run for a bus like I used to. I don’t use a bicycle anymore. I can still ride one actually but functionally it wouldn’t really be a sensible option. I go once a week to Pilates and I am lucky because it is paid for by my compensation. I really feel it keeps me moving well.

We all need some sort of income. We must be able to get food and clothes so that means either money or exchanging goods or doing something for something; in some societies maybe you don’t need money. I need a pension as I am not working now and haven’t worked for money since my head injury.

The way the letters DLA [1] make a difference in my life at the moment is that every month I get a certain amount in my bank. It’s not a huge amount; £50 or £60 per week, about £250 a month, but it’s hugely necessary in my ability to go on living.

We need to use our time. The regular things I do are not very many but they are really important to me: guitar lessons, a monthly book group. Guitar is not my profession but it’s just my love of doing things in life, regardless of whether your skills are such that other people like them and want to profit from them.

There are two other things I learned in my life, before the head injury, which were very important to me personally. I learned beekeeping and kept bees for about twenty-five years, while the kids were growing up. And I learned to sail, from beginner to being good crew, when my youngest child was about five.

This week the spring-like weather brought me back to the allotment. It’s funny how much it becomes part of your daily life because it is your particular given space and it needs ongoing simple, practical things like digging and weeding and clearing and planting. It’s quite a lot to cover for one person, especially my age. This week I spoke to a friend who lives in my street who, fingers crossed, might share my space.

I did lie in bed one day thinking ‘do I really need the allotment?’ but there is such a pleasure in picking your own things and in using them, making things like crab apple jelly and sharing them with family. So I think at the moment I will keep it going.

I speak to my mum every day, often many times a day. For at least six years after her injury, we used to write a weekly schedule for her together. If she was going to a guitar class, for example, we’d work out what time she’d need to have her rest (her daily rest, to manage fatigue), what time she should wake up; set her alarms on her phone; how long to get ready, the time to leave, and then maybe book a taxi to bring her home.

We disagreed for many years about the need for taxis. My mum has always seen them as a luxury or an unnecessary expense. But when she’s tired, or something has been intense (like seeing a film or exhibition – because she really lives them, often crying with emotion, happy or sad) her balance is worse and her walking is unstable. Mostly she can’t recognize it, even when you see her lurching and point it out. So we book her taxis. If she says she doesn’t need it, we ask her to do it for us, her children, so that we won’t worry about her. That’s a reason she accepts. And in the past few years she has accepted it as part of her life. She’ll organize it herself now.

Often our phone calls are about little decisions that cause confusion. My mother can have an erudite conversation about the book she’s reading, then talk about waking up in the middle of the night and listening to the birds, and they all somehow become fused with a decision she needs to make. I’ll talk it through with her, firstly working out what the decision or dilemma actually is. It might be buying a train ticket, and then separating her reactions to the book from the need to buy the ticket. We’ll come to a decision and work out when and where she will get the ticket. She’ll be much relieved and say how good it was to talk to me. This will take twenty minutes or so. On days when she’s really muddled I tell her to just leave it, go have a rest and I will pop round later to talk. There’s no point going over things when she’s not in the right frame of mind.

It feels like my mother is interested in everything. She finds people fascinating, engaging in full-on conversations with strangers and friends alike. But sometimes she has problems with working out boundaries. And she doesn’t want to cause trouble for others, or be a burden. Her default mode is not to ask for help, but then she’ll try to do something that’s beyond her and get in a pickle. So we remind her to call us. Just give us a ring. It’s better for us to do a small errand for her now, than spend three weeks looking after her because she’s had a fall. We use her fear of being a burden to us to persuade her to actually contact us more.

It’s like my mum is the swan swimming elegantly above, doing all her interesting activities, and my sister and I are the feet, paddling fiercely underneath the water.

You need someone in your life that you can ask when you can’t make your mind up. I speak to my daughters on the phone every day. They give me very good practical ideas when I feel confused, which helps me make decisions and not regret them. This morning, my daughter Alix came round to help me make a list of things to do today. There are things I thought I was doing every day but I’ve somehow slowed down in getting them done.

I feel lucky to be able to manage movement and making food and things like that on my own. After the head injury, you’re not really personally controlling your life day by day. It is being organised and things are going on thanks to other people doing them: carers, friends or family. I feel lucky to have got a sort of individual ability, which I hope I’ve slowly gained over the weeks and months and years since the head injury, to care for the things that we’re talking about: look after yourself every day, get up, go to bed, write, read and do whatever things are normal to you.

Then there are the things you need to do like getting in food or having your hair cut or having a bath. Having your eyes tested, your teeth pulled out. Getting proper sleep – a lot of people have difficulty sleeping. We need to allow for those sorts of things because they are regular things within your life. Family birthdays and reunions, special occasions. If someone is ill you go and give them a hand or take them something.

A support worker – a friend of my daughter – comes once a fortnight and helps me organise my diary and all the things that are going on, or book tickets for trains and that sort of thing – very helpful. And I have a cleaner every fortnight for two hours.

I am, in my own way, running my life, but also I feel it’s a complete muddle. It’s difficult to sort out what things you do need and what things you don’t. Finding things; packing bags; unexpected invitations; do I do this or do I do that?

I feel I need to get life back onto a simple level; it’s too complicated in many ways.

I have all these boxes with old stuff in them that need sorting out. Who’s going to make a programme to do that? I have to; but again, I am not good at deciding when. I want to sort out all the things I have so that I’m in a room with a table, with the absolute basics of what I need to live – what, in my own mind, I know is necessary. The other things I’d like to give away to people I like or who want them.

Simplicity may not seem to be a big responsibility or a need but, in a funny way, it is. We need to be able to convey thoughts.

I meet my grandson, Ruben, at school on Mondays at the moment, which makes it more practical for my daughter Alix to get her plans going. She works three days a week and she needs help on those days so that she can continue her work. Ruben finishes school at half past three and the school is not too far from here so I usually meet him and we come home together.

Usually he has a half hour guitar lesson – which I pay for and is not hugely expensive – with a lovely guy who comes to my place so I don’t have to go out, someone I luckily met through my other daughter Leila. So that is one of the things we do. We play Ludo or canasta – those odd things you used to play when you were a kid – and do jigsaw puzzles and that sort of thing.

Sometimes he sits on a cushion and reads the old kids’ books I have got leftover from my boys and girls, mostly Tintin or Asterix. I also found some old children’s books that I had as a kid. My teacher at primary school used to read a story to us every Friday afternoon. Once, when I was about eight or nine, she was reading this book called Chang, by Elizabeth Morse, and I was absolutely wrapped up in it. It was about a little boy who grew up in a jungle village in Siam, in what would now be Thailand. In the story there’s an elephant that is born white and in Thailand they are very special; you have to give them to the King, a bit like finding gold. So the story is partly about the little white elephant. The elephants, when they want to die, go to a place where they don’t let humans or other animals in. It is like a secret graveyard in the forest and this little boy is one of the very few people who see it. The boy gets separated from his family because there is a forest fire. He rides on the little baby elephant and the other elephants don’t kill him.

I found that I still had this book and I remembered that when I was about Ruben’s age it was making a big impact on my life. I started reading it to him a few months ago and he is absolutely immersed in it now, which is really amazing.

Things you grew up with become part of your life – that is all I am really trying to say.

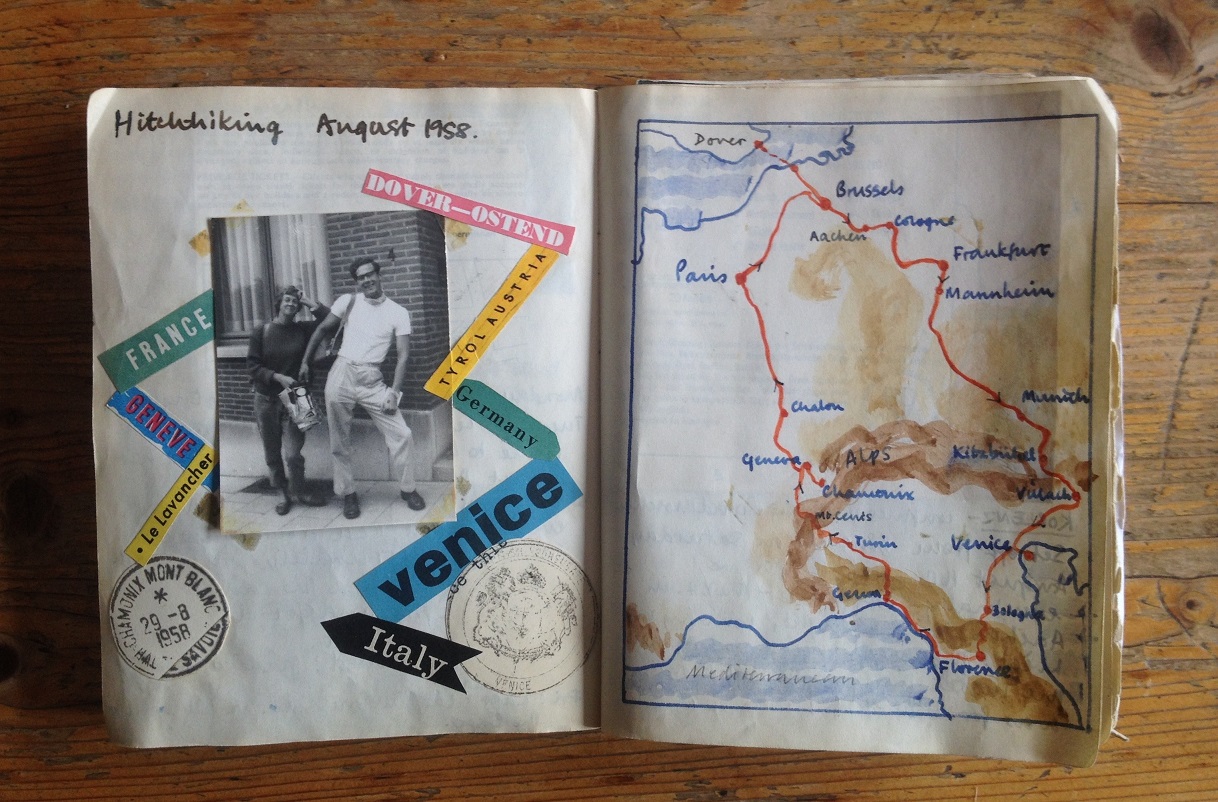

When I was a kid I used to go to school with my older brother. He was someone I followed around a lot. In a funny way he has been an example to me all my life and still is, I think. The very first travelling he did in his first summer from university was to hitchhike to what was then Persia. He went all across Europe and through Turkey and into Persia and he took photographs as he had been encouraged to do all his life by my parents. I was really amazed and inspired by that travel and those pictures. So in a funny way, even though it might sound adventurous to go off on your own I never thought about that. I just used to follow in his shoes and go to places I was curious about. Anthropology was one of my favourite subjects as a student.

My offspring have always been interested in travel as well and they have all gone to different places. My daughter Leila speaks Russian and has lived in Poland and in Czechoslovakia. So I think within your own family and your own upbringing you learn different things and learn to do different things.

I came to live in London after I left school. London itself is a very international city – it always has been, pretty much, since the Romans came nearly two thousand years ago. I feel lucky in many ways living here and getting to know people and bringing my kids up here.

I feel that now, regardless of how much I ever forget, my day by day life goes in a pattern. It is partly due to the way I grew up. There are things that I learnt from growing up from my mum and dad and my brothers and sisters: the reality of being in a group. Even after your children have left and got on with their own lives you sort of keep going that way. Being a grandma to Ruben, Eddie and Eva has been one of the most wonderful changes in my life. Children grow fast and their growing-up, with all the new technology, helps me get used to change.

All of us need that love and care in order to get through life, because otherwise it would be so empty. How would we get by if we didn’t have that? It’s like with any creatures, not just humans, any animal – that’s partly why we get so much pleasure out of nature, I think, because we see that in other creatures as well. The social and the living side of life.

The first thing that happens is a kind of inversion. I was thirty years old and I was suddenly the parent. I’ll always remember how she looked at me in the early stages – completely without flinching, like a newborn baby. It’s a kind of rebirth. It’s very freaky to see that in your own parent. And it’s so sudden, so total. I had to feed her, change her clothes, take her to the toilet. It was very primal. And yet she could talk to me – she was like a baby that could talk.

In time things gradually slid back and I realised, ‘actually, my mum’s cool now. She can cope.’ At first it was hard letting go but then I suddenly thought, ‘I want her back – I want our relationship to be about us again’. We’d got to a place where she could take that role in the family again – and be Ruben’s granny.

I know I’m very lucky to have had that come full circle. She did have an incredible recovery. I had to learn to grieve a little bit for that part of her that was lost. But also to let go of that and accept who she is now.

It was odd on a personal level that I became a mother about two years after her injury. Mum and Ruben shared something quite strange. He was her first grandchild and she was just strong enough to care for him and at the same time it was like she was growing up too. It was extraordinarily beautiful watching them together. She could enter into his child’s world in a way that I almost felt envious of. I would go to the shops and come back and she would have a tea-cosy on her head and they would be totally in their own zone together. They still have this wonderful relationship, this strong friendship. I appreciate hugely that she’s there to share her wisdom and stories with Ruben. Sometimes I have to remind her that just because she’s not earning money and cooking meals for everyone – she still has this huge value as a figurehead for the family, and her history is very important for us all.

Mum is very honest and philosophical. I enjoy the conversations we have now. She has a perspective and a simple appetite for life that I find useful – it reminds me what is and isn’t important. I think there’s something when anyone goes through a near-death experience – of valuing and relishing life in a more vibrant way. I’ve piggy-backed on some of that!

It’s helped me in life – the realisation that in thirty seconds your life can change. It’s just the luck of the draw. But also not being scared of talking about death. There’s no reason to be scared or shy away from it. It just is.