When he would start to sing, people were astonished. Their jaws would hit the floor. He was amazingly talented.

When he would start to sing, people were astonished. Their jaws would hit the floor. He was amazingly talented.

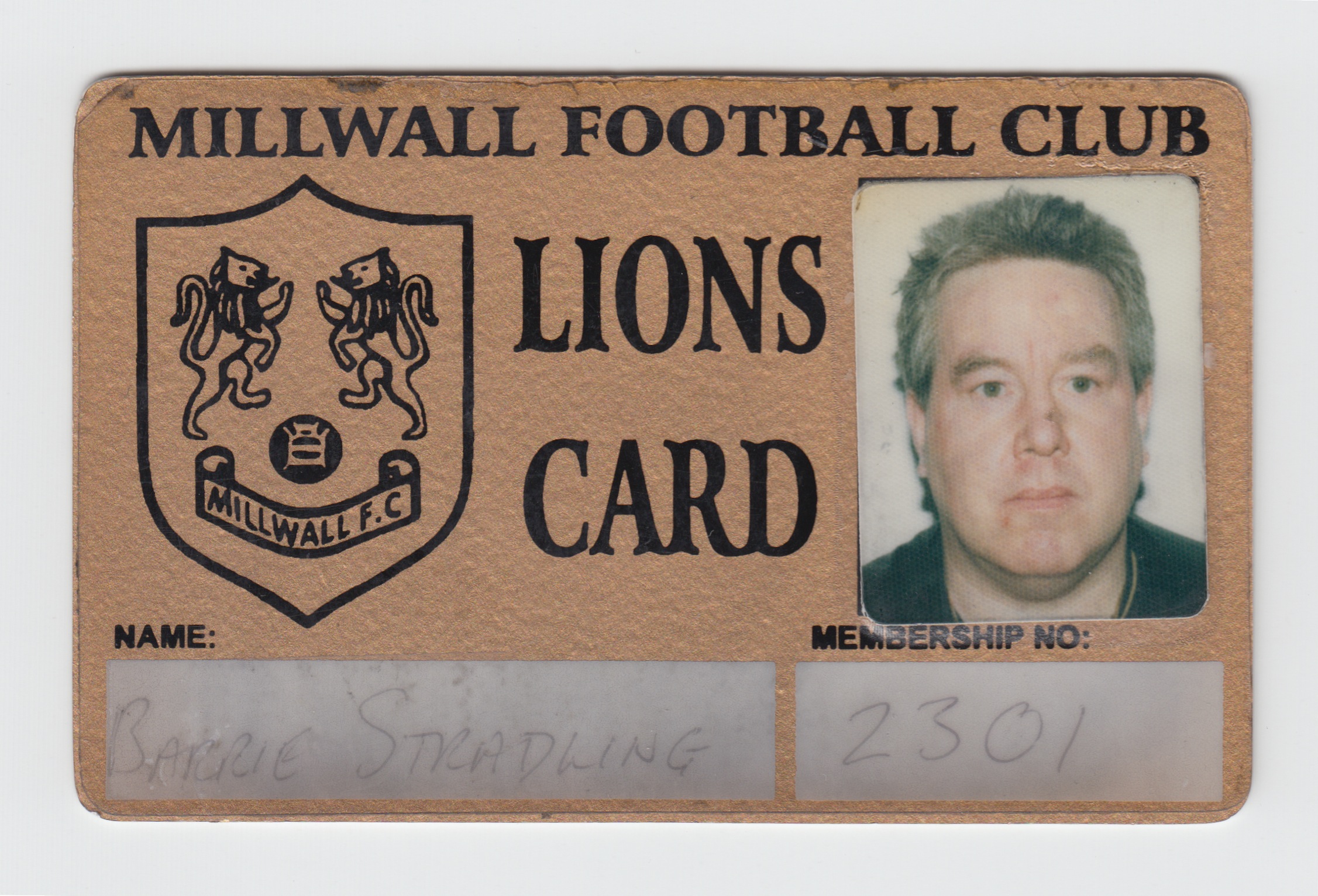

Music’s the big thing for me – that and Millwall.

I’ve written umpteen songs, done hundreds and hundreds of gigs. But at home we used to listen to The Navy Lark, Round the Horne – more comedies than anything else. My dad used to love Don’t Laugh At Me Cause I’m A Fool by Norman Wisdom. So where the musical influence comes from, I don’t know.

My dad’s sister’s son George used to play lots of musical stuff like Tommy Steele, Max Bygraves and whatever. I used to listen to music there more than at my house.

Lots of my family lived close by in East London. There were three of us in the house, but there were twenty-three of us. Most of my mum’s family lived on the same street, so we’d see them all the time. My cousin Roy lived on the other side of the street when I was growing up. He’s the reason I support Millwall – I’ve blamed him so many times!

When I was at primary school I was in a choir. We sang at the Festival Hall. Then my mum and dad put me on stage in the Isle of Wight in a singing competition, singing a Beatles song I didn’t know.

I preferred The Monkees, to be honest with you – I saw them with my mum in 1967.

When I was born, Whitechapel was a Jewish district. Clothes shops, beigels, Jewish bakeries, Jewish restaurants – when I was a boy that’s what it was. Limehouse used to be a Chinese area and it was not where it is now – Limehouse Station used to be Stepney East and Limehouse was on the outer edge of the Isle of Dogs. The East End I know is not here any more. It’s changed so much because a lot of people have moved out of East London. Things change; the world changes.

My mum used to sing My Yiddishe Mama at weddings and I thought ‘why is she singing that?’ I actually didn’t find out till she passed away in 2007 that her mum was partly Jewish. I thought it was odd that she wouldn’t tell me.

My dad’s scrap metal yard used to be where the Rotherhithe tunnel comes out in Limehouse. He died of asbestosis in ’78. In ’95 I said to myself ‘I want to buy somewhere in the East End.’ They’d built a complex of flats right by the spot where my dad used to work. So I thought ‘ah, this looks good’. Twenty years ago there was nothing round there – it was completely empty. Now it’s all singing and dancing, all built, all done.

At grammar school there were lots of people who wanted to be musicians. Everyone wanted to try and do it. I saw Zeppelin in ’71 I think it was, and then my favourite singer was Ian Gillan out of Deep Purple.

I couldn’t play – I have not got the patience to learn anything, bass, guitar, keyboards – but I could sing. I thought, ‘I’ll do that’. We all loved heavy metal – Zeppelin, Sabbath, Purple. I saw Zeppelin five times and Sabbath four.

I met Keith and Steve in ’75, when I was seventeen. They were in a band called Aquila and they used to go to school together. The band was like the Doobie Brothers or Wishbone Ash – white funk. We met at a pub called the Spreadeagle where they used to play Bob Seger, Thin Lizzy, Bruce Springsteen, that sort of stuff. My schoolfriend Dave and I heard them talking about how they wanted a singer and a drummer. We thought, ‘yeah, we’ll do this’. Dave was a drummer and I was a singer, so that was it – we were in the band.

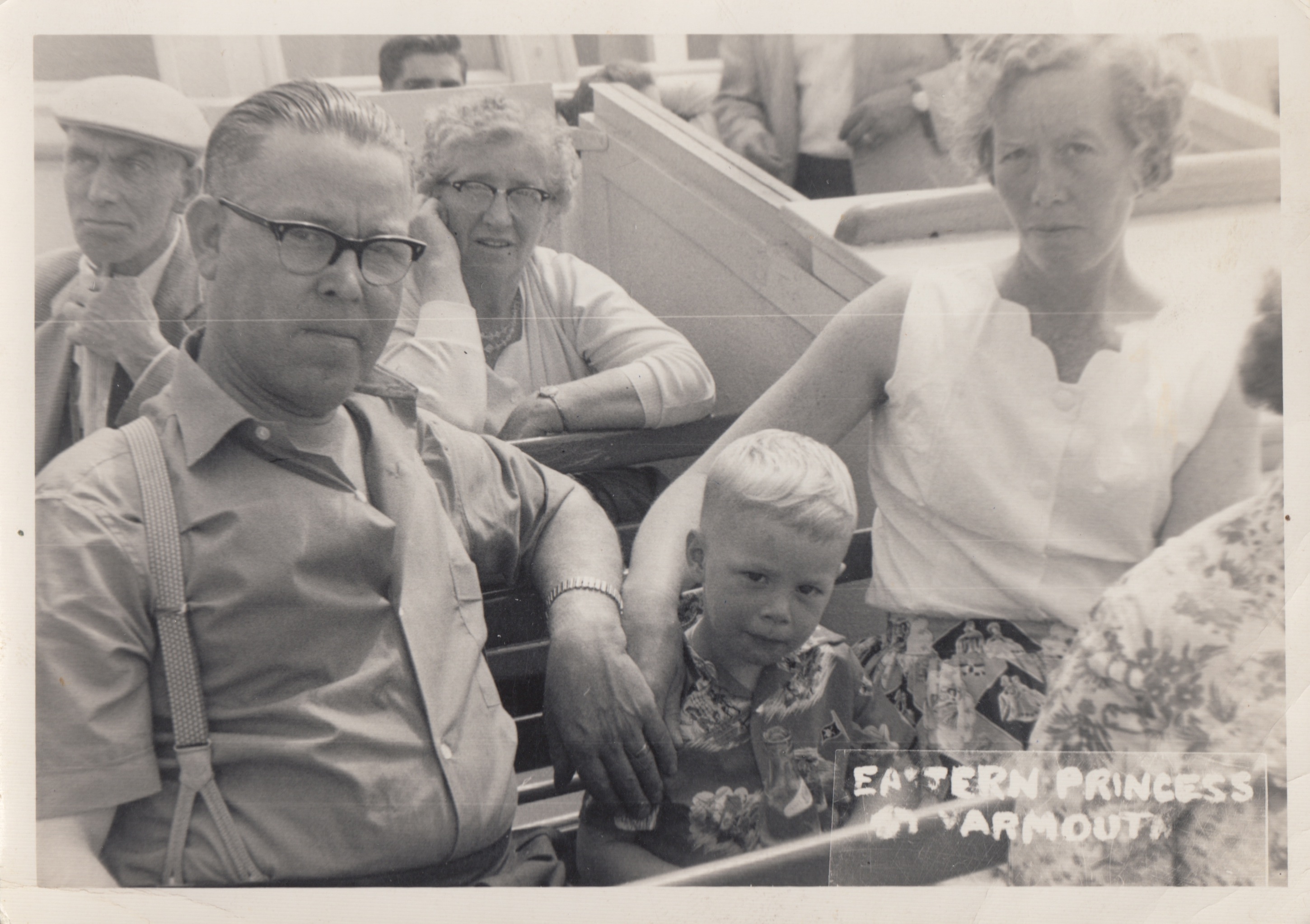

I’ve been in a number of different bands since then, but the one that lasted was the Pontinentals a.k.a. The Funk Soul Brothers. When we formed we had a Greek drummer, Makis. I thought ‘let’s call ourselves The Continentals’ and then I found an old T-shirt indoors that said ‘Pontinentals’ from the first trip I ever had abroad to Sardinia in the 1970s. But people didn’t understand what sort of music we played so we changed the name to The Funk Soul Brothers, to idiot-proof it. Soul. Funk. Funk Soul Brothers.

The line-up has changed over the years. Makis left; he got a musical job in Greece. Then Percy – the keyboard player – left. It was blind luck – we were at the studio and this keyboard player Dave was saying ‘I need to find a band.’ Marriage made in heaven. And Dave knew a lot of horn players so they got on board as well. Over the years we’d bring people in from all over the East End to join the band. The bass player, Steve – his brother-in-law was a drummer. It’s incestuous, pretty much, the music scene in London!

Singing is something I’ve done alongside different jobs. I started off in the print and I’ve done typesetting, advertising and freelance writing. I was a carer for my mum when she got ill with glaucoma, so I put work on hold for a few years. I’ve written three books about football and I’ve worked in financial services. I did session singing in the eighties for a while but I didn’t have contacts – that was the trouble. If you haven’t got contacts you can’t get into the business even if you’ve got the greatest voice in the world.

There was a club in West India Quay called Soul Cellar. The first time I sang down there, in 2005, it was with Jamiroquai’s keyboard player – it was that sort of level. I used to sing every Wednesday with the singer down there, Fil Straughan. He said to me “us two should be a duo”. Then I had the accident and it went backwards.

I met Barrie about seventeen, eighteen years ago at a rehearsal studio. I was talking to a guy, asking him if he knew anyone who needed a keyboard player. Barrie was standing next to us and said ‘We need one’. I joined the band and got to know Barrie over the next few years. We played many, many gigs together. It was nearly fifteen years I was in the band.

Playing in a band is like being in a football team – it’s a team sport. You’re travelling together, setting up together, dealing with issues together, dealing with different people. Great fun at times, boring at others, sometimes frustrating. You have ups and downs. But you see your bandmates in a whole range of situations and you get to know each other really well.

Barrie was a very popular, communicative – a very trustworthy guy. Very, very well liked. He was never overly-opinionated about anyone. Very accepting.

It was amazing how wide his social circle was. You would be at a gig and suddenly you would notice a household name in the audience, and sure enough, it would either be a friend of Barrie’s or somebody he knew through another friend. You got the impression that Barrie knew everyone. He was very witty, sociable. He was rarely the spokesman for the band – people just knew him as Barrie from the pub, or football or whatever – his humility was one of his endearing qualities. He would never brag. So when he would start to sing people were astonished. Everybody I ever knew – their jaws would hit the floor. He was amazingly talented. He could pretty much emulate the best: Otis Redding or one of those guys. As a soul singer he was up there.

The accident happened in November 2006. I was in a pub in Mile End and I crossed the road at a split crossing – a road I’ve crossed hundreds of times before. I crossed over the first part fine on the red light. Crossed over the second part, green man, a car hit me. A hit and run driver knocked me straight up in the air. I fell on my head. Fractured skull, grade three coma, spark out. I was in a coma for six weeks, hospital for seventeen weeks. The driver was done for not stopping and not reporting the accident. He got fined and he got his licence taken off him for six months, but I was practically dead so it doesn’t relate at all.

In East London they don’t stop half the time, they go straight through. Don’t look at the lights, look at the driver!

I’d been having a drink with my mate Steve from the band. He was going the other way, towards Bethnal Green, and he heard the crash. He turned around, found out it was me on the floor. He came and put a coat over me. When I was recovering after the coma I said to Steve “don’t tell me anything”. I didn’t want to know the details. Denial, I think. It’s almost like if you ignore what happened, you didn’t have it. Not me, mate! I think it’s a common thing with brain injury.

The first hospital I was in was the Royal London. Then I moved on to Mile End Hospital as a stopgap before a bed became available in the RNRU, the neurorehabilitation unit at the Homerton. I was in hospital thinking, ‘I wish I could still sing’. It was the main thing for me. In Homerton the band came to see me and they said ‘could we actually come in here and play?’ So I asked the doctors and they said ‘yeah’. We rehearsed in a little room with a pool table to see if I could still sing. My cousin Roy brought in loads of lyrics.

I could still sing, but my memory was all over the place. After I came out of hospital I was using typed lyrics, typed arrangements, which I never ever used before. Before, I would go and sing anywhere with anyone. But the brain rewires itself as a different thing. The injury did affect the performance because you’ve got to look at the page all the time rather than just do it from memory. It’s not as immediate. Before, eighty songs – I just knew them. Now, I know bits and bobs.

They let me out of hospital to go to the football – Millwall against Leyton Orient. My friends had to help me up the stairs. We lost 5-2; I said “take me back to the bleeding hospital!”

We first saw him within a couple of days of the injury. We’d done one of the best gigs we’d ever played that weekend. It was a ticketed gig for friends and family. We had an amazing line-up. Barrie had sung probably the best he’d ever sung. It was quite disturbing – to see him with all the wires, the tube down his throat. To see him go from such a high to such a low within just a few days. It wasn’t easy.

When he was in the initial part of the recovery – in a coma, or bedbound – I used to visit him as often as I could in Whitechapel or, later, at the Homerton. I went to see him at least a couple of times a week. When he was in the Homerton we used to go and play music: some of our set, just acoustic. The doctors said it would be good for him, to help him recall things. It was tragic to watch him try and sing – it was terrible in the early stages. But we kept going to see him, hoping he’d get better.

When he was well enough we took him to the rehearsal studio. His voice was improving but we could see his memory wasn’t as good any more. When you’re singing in a band you have to know an awful lot of songs and lyrics. We spent quite a lot of time helping him relearn them but there were still gaps. Normally if you’re a singer and you forget the words you just busk along and then it clicks again. With Barrie he would just stop and look confused. And that’s hard to get out of!

The first time I got back on stage after my brain injury, we did a charity gig for a schoolfriend and former bandmate, Chris, who had passed away while I was in hospital. He was three days younger than me. Because I hadn’t been playing for a while and I’d been in hospital we decided to get a girl singer on board as well. I went karaoke, too, because then you can read it off the screen. Magic! Then I did open mic stuff with a live band. It took seven years, but I’ve got back to how I was as a singer. The memory’s better than it was. Whether it’s the same as before I don’t know – don’t think it is.

I’ve never had stage fright. I think using nerves is a good thing because you’ll be more soulful. I don’t get too nervous because if you’re in a band that you trust you’re not nervous. If you’ve got someone like a drummer who always overplays then you’re nervous about what they’re going to do. I’ve always played with musicians who’ve been very tight. I don’t mean tight not buying you a drink, I mean in a band sense.

The band have always been very supportive of me, especially Dave, the keyboard player; Keith, the guitar player; Steve, the bass player, who was in the band – he’s not in the band any longer. We’ve been friends forever. This band’s been going for 20 years or so. The trouble is, we’ve not been playing. The last gig we did was October 2013. I’ve done lots of open mic things – I’m still singing places. But we’ve not done full length gigs like we used to, two or three times a month. We used to play lots of pubs but with an eight piece band financially it’s not worth it. Rehearsal, petrol, it doesn’t really work.

People always say ‘How’s Barrie doing?’ and I always say he’s ninety to ninety-five percent recovered. Then they ask what the missing five per cent is. I think part of it is about emotional extremes, the other part being his short term memory. Things that you or I would find a little bit taxing might push him to the end of the spectrum – he might get very angry or upset.

At gigs you get people coming and making requests about songs. Before, he might have said “I’m sorry, I don’t know that one. ” Now, he might just tell them to eff off. That’s the sort of thing he just doesn’t cope with that well now.

His humour is more forceful. Rather than using witty language he might now just swear. Or he might just shout out ‘Millwall!’ in the middle of a set if he saw someone wearing a West Ham top. Completely inappropriate if you’re playing a wedding! In some ways it’s funny, but in some ways it’s a bit uncomfortable. What he thinks is humour might be inappropriate in some contexts. I suppose it’s sometimes not being socially aware – of where he is or what he’s saying.

Some people find that uncomfortable and difficult to deal with, so they might not choose to put themselves in that situation.

Barrie was always tenacious in a positive sense, but now that tenacity can be a bit unrelenting. Before his accident he would never miss details; he was really reliable. But after the accident the details became something he would latch onto and be so unrelenting it would become overbearing. He’d be phoning, emailing and texting you about the same thing, and then following up almost simultaneously.

I didn’t know anything about brain injury. You’re in hospital. You think, ‘oh, I’ll be alright tomorrow’. But it’s not a quick fix.

People around me could see things that I was doing wrong. Cognitively, it was odd. I was repeating things over and over again, interrupting people. You’re not sure your memory’s working, so you say things as soon as they come in your head, before you forget them. I kept asking people, “Am I okay?”

You have to relearn how to function. How do you learn to walk up the stairs? You’ve had it since you were a kid. How do you learn to read? Partly, it’s a confidence thing. Singing, writing. Can I still do it?

Friends told me I was more aggressive. Even now, I’m more likely to get involved in arguments than before. If I thought you were doing something wrong, before I might think it – now, I’d just tell you. I couldn’t see why I was in hospital, I couldn’t see who was helping me, who was there supporting me. To me, they were against me. I overreacted to things. I couldn’t see the reality of it because my memory was bad. Now, I can understand how the world is, but at the time I couldn’t.

I don’t think you can see what the differences are yourself. It’s more obvious to other people. I had to ask people.

The neuropsychologist told me I have difficulties dividing my attention – switching from one thing to another or paying attention to a couple of things at once. What I was able to do before, I couldn’t do. It’s taken years and years to edge back into it, d’you know what I mean? You don’t go back to where you were.

I would say Barrie’s got two very clear passions in his life – one is Millwall football club, the other is music. He’s carrying on doing the football, he’s as passionate as he ever was. That’s great.

With his music, many people have supported him along the way. He still has an ability, and it is improving day by day. Maybe that spark isn’t there the way it used to be, but considering where he has come from in a relatively short time, it isn’t out of reach – certainly not for Barrie.

If a band’s split up, friendships might continue but they tend to fade after a time because your common interest was the band. Some have kept in touch a bit more than others. I think those that weren’t close to him just fell by the wayside, but many still ask after him, another testament to his endearing character.

The greatest challenge is getting a new band together, made up of individuals who are willing to accept some of the issues he has, especially in regard to how the volatility of his emotions might affect his presentation skills, or his capacity to remember lyrics and running order.

I imagine it must be quite difficult to accept that, but whether he’s aware of it and just deciding to push ahead, or if he’s not so aware of it, I’m not sure. What I do know, is that his other endearing characteristic is his positive attitude, and his ability to channel his tenacity into overcoming these challenges and move on to pastures new. In all honesty I don’t really know how much his social life has changed because I don’t see all parts of his life. I know he’s doing other things, with Headway and other charities. He’s never given up – he’s pushed and pushed and pushed. He’s never relied on anyone else in his recovery.

I give him the utmost respect. Most people stood behind Barrie – he always inspired loyalty. People want to help him. He hasn’t stopped. He doesn’t stop! He’s taken his life in a slightly different direction – so I suppose he must recognise where his strengths are to some degree.

It’s a shame about the band, I do feel sad about it sometimes because it was incredibly good while it lasted. I’m not playing much any more, mainly because of personal circumstances. Every now and again I’ll get a call to do something or other. But I’ve got three kids now. My daughter was born just around the time Barrie got hurt. And then the twins. Things change. Not many people can make the kind of commitment you’d need to carry on in a band in the long term. Most of us have families now. Barrie would have toured the world if he could!

I went straight back to work in financial services, which was a mistake. They paid me my full wage whilst I was off work in hospital, so I thought I should go back as a thankyou to them. When I was in hospital I thought ‘I can do work easy’. I was discharged in March 2007 and was back to work in April. I did shorter hours to get back in the swing. The company adapted my hours when I went back to work. Lots of employers don’t adapt, so you go back in the deep end, like you don’t have any problems at all.

When I came out of hospital, things that were easy before were a nightmare. Just getting a bill through the door, I thought, ‘it’s a bill, what do I do with it?’ I was panicking. You don’t realise what skills you’ve lost and what skills you’ve still got. I used to do investment portfolios, admin stuff, running the office. It’s all stuff where you need to multitask. When I was back to work I realised it was too much. Filling out forms – how do I do this, how do I do that? Yomping across London to Mayfair every day. It was too much, it was crazy. I shouldn’t have done it. And then my mum died in July that year. I was taking care of her all the time, until the accident.

Everyone at work was supportive of me but I couldn’t understand that they were. I thought, ‘ah, it’s a nightmare’. In the end they said ‘we don’t think you are functioning as you were, so I think we have to let you go.’ They let me off after about six, seven months.

You do think about how much you’ve lost in your life. You think, ‘eight years have gone to waste’. The personal injury case lasted four years, and I had no money coming in from anywhere. The only money I had was my life savings and my mum’s money after she passed away. It was some money but just some. My cousin Roy was involved in the whole thing. He took me to court and he took me to solicitors. He did all of that sort of stuff so he is like a litigation officer now. At least there was support there, because doing it on your own – good luck!

I went through loads and loads of stuff with solicitors. The solicitors I had got the claim okay but didn’t understand brain injuries. They didn’t do any financial assessments or psychological tests at all. The money was put in the Court of Protection [3] but I wasn’t told what the restrictions were, what the timescale was – anything. For me to get anything it had to go via a deputy. If you get a lot of money you might need someone to look after it for you, but I didn’t. So I had to get rid of the bloody thing.

There was a meeting with the barrister and solicitor. The barrister said “he doesn’t need this court protection at all, because he understands this more than I do”.

There’s a lot of stuff that feels like a waste of time. Stuff that gets in the way of you moving forward. Benefits. You get Atos [1] and you have to talk to their doctor. That is a nightmare, that is. You see a doctor who doesn’t know you at all and they say ‘you seem ok, go back to work’ and then they withdraw the benefits. The clinical psychologist at Mile End hospital advocated for me and they got it back straight away. They said ‘they should never have taken it away’. At that time you’re in panic mode.

My friends and family have stuck with me. We still all see each other. Friends from school, friends from football, from music, they’ve stayed with me. None of them have disappeared. People sometimes do disappear when someone has a brain injury.

These days, I’m doing a lot. I’m writing, singing. I wrote a book to see if I could still do it – I could. I help run the Geezers Club, a group of older men who meet every Tuesday afternoon in Bow. We won an award for our intergenerational work with local schools, and we’re doing a project to highlight the demise of the East End public house, called ‘Where’s My Boozer Gone’. I also do lectures for Headway East London to help professionals understand brain injury. You just have to try things out.

About three years ago I took part in an MRI [2] research project at Homerton Hospital. They showed me what was inside my head and they said, “this is where the damage is – just here” – it was a frontal lobe injury. It was weird because I had never seen my brain before. And then I did another one: TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation. Basically they attach electrodes to your head and send pulses through it and they put things on your hands and see how it triggers your body. That was all part of the MRI project but some of the brain functions don’t show up on the MRI. They said I had recovered a lot: seventy, eighty percent.

The most important thing is: if this happens to you, don’t ignore it. It doesn’t go away. You need an awareness. Meeting other people who’ve been through it has given me a logical perspective. It’s helped me understand myself.

Atos Healthcare is a company that conducts assessments on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions for Personal Independence Payments, and until March 2014 did so for Employment Support Allowance. The ESA assessment process was criticised by MPs, charities and the clergy due to the distress caused to some claimants and the high number of successful appeals by unsuccessful claimants.

MRI – Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Court of Protection – created under the Mental Capacity Act, 2005, the Court of Protection has jurisdiction over the property and finances of people deemed to lack the capacity to manage their own affairs. The Court will appoint a deputy to assist individuals who need help with their decision-making.