Maybe if you need an answer to the question ‘Why?’, you can’t fully have forgiven someone: it’s not full-hearted forgiveness

Maybe if you need an answer to the question ‘Why?’, you can’t fully have forgiven someone: it’s not full-hearted forgiveness

I remember in primary school we were all told to draw self-portraits. The other kids were drawing themselves smiling and so on. I did a self-portrait, but I wasn’t smiling, and the background was dark. I didn’t understand it back then, but that was a definite reflection of how I felt inside at the time. Back then I just thought, ‘It’s a picture of me.’

Specific details are difficult to remember. It takes me a while to think, to try to recall. Some of my memories of childhood have merged and fused together. Is that worrying? My injury has led to a lot of questions. When you have a brain injury, you’re usually just dealing with the moment, not really swaying back into the past. It’s good to walk down memory lane again and remember who you were before and who you are now. It sheds a light on you, and on areas you don’t normally think about.

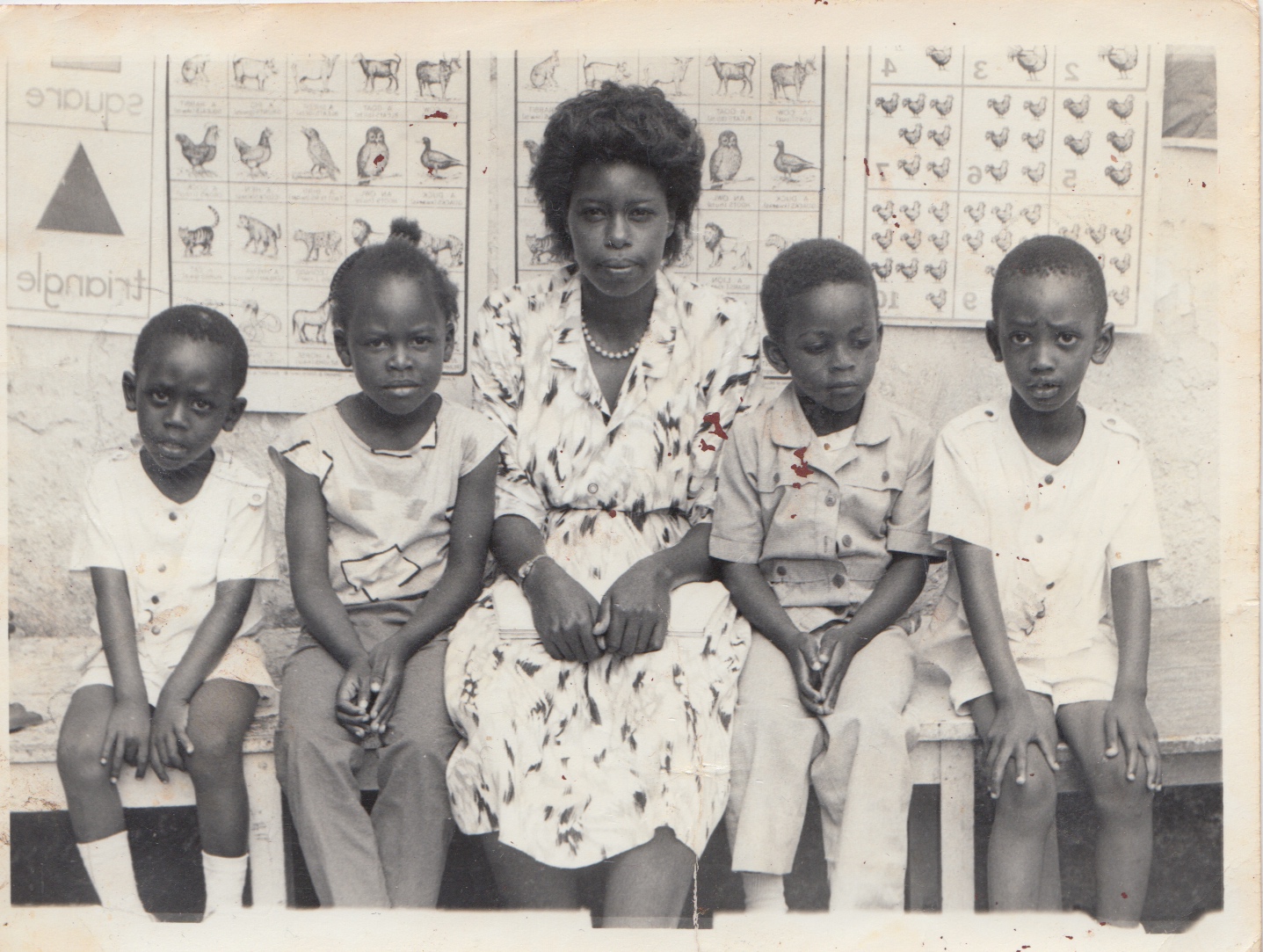

I was born in Uganda in 1982. I was young when I left. I needed heart surgery, so we came to England, to Liverpool. Just me, my mum, and my sister – I was the oldest, and she was the youngest. My brothers stayed with my aunt in Africa while my mum was dealing with me and the surgery.

The operation I had was a valve repair. I was too young to understand that – I thought I’d had a heart transplant. I thought I’d been given the heart of this other Italian kid who was on the same ward. I thought we’d swapped hearts! For a while I was telling people: “I have an Italian heart.”

When the surgery was done, we moved to London. Everything was new. I was still learning English, I was in a new place, and my brothers were left behind. Even in secondary school I was still finding myself. I still had an accent – I probably have a bit of an accent even now. My brothers tease me about it – certain words I pronounce, you can still hear the Ugandan in them. My brothers came across when they were younger and they picked up the London accent quick. My parents are from Rwanda, and the majority of my family are still out there. My heritage is Rwandan, but now, today, I’m a Londoner.

When I left school, I worked as a chef for five years while I went to college to study Sociology. Two of my best friends from school worked at this restaurant as well. One of them was from Somalia, the other was from Yemen. One of their fathers started a business abroad – he and some other people bought a big ship, and got into the cargo business. My friend’s father asked him if he wanted to work on the ship, and he asked us if we wanted to come along too. I suppose it wasn’t a hard decision for us to make – we’d been in that kitchen for five years and we were kind of sick of it. So I went abroad to work on this cargo ship. That was one of my best adventures.

The ship would travel from Holland, down to Cairo, then on to Dubai across the Red Sea. The cargo was cars, TVs, mopeds, anything. The whole journey would take a month. Being on a ship for a week feels like a month. On the way, the ship would stop at a port and we’d have some time off and go a bit wild. Our favourite place to go was Madrid. That’s where the best looking girls were!

I was an assistant to the chief engineer. I’d help him with the plumbing, the electronics, making sure everything’s at the right level. Every one of us had to help with the cargo, whatever’s going in and whatever’s going out. We all did a bit of everything.

The other guys on the ship were from all over – Philippino, Dutch, Australian. Because me and my friends were newbies on the ship, they told us some old sea tricks. They said that if you’re feeling sea-sick, you get a potato, rub it in dirt, put a rope through it and wear it on your neck: the smell of earth would balance you out. And it sounded like it could work! But that’s just what they do to newbies – you’re walking round with a potato on your neck. Of course when other people joined the ship, we passed it on. We’d have the potato on a rope, with dirt – readymade. We’d hand it to them: “This will help you….”

There was once when I almost lost my life. It was four in the morning. An oil pipe had burst, and me and a friend were on deck trying to repair it. I slipped on some of the oil – the ship was being rocked – and my back hit against the edge of the side of the ship. It would only have taken one little push, the ship just rocking a little, and I’d have fallen in the water. But my friend was right next to me, and he quickly came and pulled me back. If I’d fallen in, the cold would surely have killed me.

We’d hear stories about pirates, especially from the workers who’d been at sea for years. Some of their stories were terrifying. There was a gun on the ship, for protection – the captain had it in his room in a locked box. Me and my friends had our own makeshift weapons that we’d put together – sticks of wood with nails through them. It’s a risk we were aware of, especially crossing that particular part of the Red Sea.

While we were out there, my friends and I started a business of our own. All three of us put our money together and we started buying boat engines – buying in Germany, selling in Cairo. We knew that in Africa they loved any kind of engine that was made by the Germans, and boat engines were in demand.

There were times, of course, when you’re pulling this heavy anchor, sweating so much, you miss home. But it was probably the most peaceful time of my life. It’s therapeutic.

It was at sea that I learnt to play guitar. I’d always take my guitar and go and sit right up at the top of the ship, just playing away – imagine it – playing away, seeing the sunrise, nothing but water all round you.

That time came to an end when the business slowed – the investors were looking to shut it down. So we said alright, once we get to Holland, we’ll get off and make our way to London.

I got a job in King’s College as an electrician. I didn’t have the training, but I’d learned the trade while I was on the ship.

When I got a place of my own, a band moved in next door. I’d always hear this band playing music until ridiculous hours in the morning. One guy in the group would always knock on my door to ask for a cigarette. I’m like, “Hey, you can’t do this at two in the morning!” So I got to know them, and eventually I was jamming with them until ridiculous hours. Their manager at that time had left, so I said “I’ll manage you guys, if you keep the noise down for now.” They asked what experience I had, and I told them I didn’t have any experience, so they said, “Let’s try six months and see how it goes.”

Within those 6 months I sorted out free studio time and a few gigs, so I was doing well for someone with no experience. That’s how it kicked off, and I was their manager for four and a half years. They were called ‘A Band Named King’. That name wasn’t one they decided – after they did a gig in Liverpool there was this homeless man outside, and he saw one of the guys with a guitar on his back. He called them over said “Are you guys in a band? Do you have a name?” And he wrote down something on a tissue and said “Call yourselves this”: A Band Named King. I liked that name – a name should have a story behind it.

The last gig I organised for them was supporting Noel Gallagher’s new band. I had some big interviews lined up for them too – interviews that would have really put them out there.

It was New Year’s Day in 2012. I was on my way to see my girlfriend at that time. I’d spent New Year’s Eve at a house party, but she hadn’t wanted to come along. I was riding my bike through Camden. The last thing I remember was seeing this van.

Rehabilitation Services Discharge Report

17.12.12

Mr Kabeja was admitted to UCLH on 01.01.12 following a road traffic accident. CT scan showed right frontal subdural haemorrhage [1] and midline shift to the left [2]. Mr Kabeja was taken to theatre for craniotomy [3] with evacuation of blood clot [4] and insertion of intracranial bolt [5]. Later he had further surgery for bone flap replacement [6]. After the operation he had raised intracranial pressure (ICP) [7] and the bone flap was removed again when his ICP continued to rise. A small frontal lobectomy [8] was also performed.

When I woke up I’d been in a coma for three weeks. I didn’t know what had happened. I had these fabricated memories – I think they’re called ‘post-traumatic amnesia memories’. That’s the only thing I had in my head, but at the time I didn’t know they were fabricated.

One of the memories I had was that I was expecting twins with my girlfriend at the time. I remembered keeping the picture of the ultrasound scan in the pages of one of my books. I was looking for that picture everywhere, asking the nurses for it. I remembered taking photos of my girl with her stomach being big. I was really looking forward to having twins. But there were no pictures, there was no scan, and my girlfriend wasn’t pregnant.

If you’ve been in a coma, there’s a gap in your mind, so your sub-conscious fills up that gap with memories it creates. Those memories feel as real as any other memory. And they’re not created from nothing. For example, the kids relate to my sub-conscious because around the time of my accident everyone I knew was having children, and twins came into the picture because there are twins in my family.

My girlfriend had to go home to France, and she couldn’t put her flight home any further back – she’d been putting it back week after week. Poor girl, she went through a lot. On the third week I came out of the coma, so I got to see her before she left. She said she had to go. Of course I understood. The relationship was fairly new. I wasn’t able to ask her about the twins. Those memories were there, but I didn’t ask, I don’t even know why. I suppose there was just so much in my mind.

Later on I even questioned if I really saw her. I remember that she was wearing the same top she wore on our first date. That made me wonder whether that was fabricated too.

I had another memory, associated with the kids – something I thought I did for my girlfriend at the time. She was already in France, already pregnant, and it was Valentine’s Day. I’d sent flowers to her door in France, and talked with her on Skype, and had a meal with her over a laptop. I told that memory to my physiotherapist. She can remember looking into my eyes, seeing how much I believed it. And she believed it too.

When I explain that to most people, they say, “Oh, it was a dream” – but I don’t acknowledge it as a dream. It was a memory – a real memory. Not based on real events, but a real memory. I’d recall those memories like I’d remember something from my childhood – there’s literally no distinction for me. It did make me doubt some other memories – not the ones from my childhood, those were secure – but from the year or two before my accident.

In my mind the accident didn’t happen how it really happened. I thought I was on my way back from a job interview with the secret service. I believed the job was mine: ‘Director of Operations’ at MI5! After I woke up, I was telling the world. I believed everything, so other people accepted it too. You wouldn’t believe the damage control I had to do when I realised I’d been wrong about it all. All the people I told – my best friends, my brothers – I suppose they knew something wasn’t right, but because I was in such a fragile state, they didn’t want to confront me. They just let me go on with it.

Reality started to hit – slow but heavy, heavy realisation. For a while I wasn’t sleeping well on the ward. Thoughts kept going on repeat and repeat. I had to speak to someone, so I spoke to my psychologist. Before I spoke to her, I went online, and I started researching dreams. I remembered Sigmund Freud was the best analyser of dreams. And there was one quote of his I found, about the sub-conscious mind, and reading it I instantly felt – not relieved exactly, but it made me feel that there could be an explanation for these fabricated memories:

“The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.” – Sigmund Freud

I was so wrapped up in how good it would be – having twins, a new job – that I was not actually seeing evidence that was right there. Those hopes and ideas and plans I had been making for my kids in my mind just vanished. It was tough, but I couldn’t let it get to me to the point of depression. My physical state was not good at all, so I didn’t want to give my mind more heavy things to think about.

In that fragile state I was looking for signs – what’s going to happen? Will I use my arm again? If something happened out of the blue I’d look at it and think, ‘what does that mean?’ – questioning the whole chain of events. I‘d feel that it couldn’t just be a coincidence. I’m a religious person. Not because of what’s happened to me, but the experiences I’ve had go with a feeling that was always there. I believe there’s more out there than stars and planets. Just look at how complicated the human body is.

I had so many thoughts going through my head, I didn’t have time to analyse how I felt. Those feelings were overshadowed by my false memories.

I’ve spent many days, many evenings, indulging myself in those thoughts, those memories, laughing at them. Laughter, not because it’s funny, but out of frustration – like an outlet. Even though they were fabricated, those memories still got me through some tough times. That’s why I don’t regret them. I thought, if I’m going to have twins, I need to work hard to get myself strong again, strong enough to pick up my child. So that was a motivation.

What stuck with me more than the memories themselves – which I remember as clear as any other memory – is the disappointment of finding out that they were not real. Even if I was strong and kept strong, I still remember that disappointment. It made me question everything. Even to this day, I never let myself get absolutely happy with something until I’ve achieved it, and even then I never fully let myself go. Even if I know something’s true, I never let myself get too happy, in case it’s not true, or it goes wrong. I know it’s there, and it’s real, but I still hold myself back. I never let myself feel secure.

Rehabilitation Services Discharge Report

17.12.12

Psychological Presentation

Mr Kabeja expressed some concerns regarding the memory deficits he experienced following his injury, particularly the lack of memory of the accident itself and a number of confabulated false memories [9]. Initially this resulted in him having little confidence in his current memory as well as anxiety about whether he could “trust” his memory now. After some pyscho-education, Mr Kabeja has a greater understanding of why he developed the false memories, and has accepted that this process of confabulation is not ongoing.

I keep a healthy diet for my sub-conscious now. That’s the only diet I’ve ever managed to stay on. I don’t watch horror movies – even the trailers. My dreams are very influenced by what I watch. If I watch TV and have a little snooze and a little dream, I’ll dream about what I’ve just seen. If there’s an argument, even if it’s not me arguing, I walk away. If I’ve done something, and I’m thinking, ‘Oh gosh, why did I do that?’, I try not to spend time dwelling on it. I try to find a solution instead. All that negativity stays with you.

What would you rather have healthy, your body or your mind? If the mind is not healthy, the body won’t work.

While I was still at the hospital in Putney, my physiotherapist took me to this accessible sports festival in Essex. All these different sports had their stands out. I was wondering about getting into cycling – because my accident happened when I was cycling, if I got back into it that’d be a fitting end. On my way out, I walked past the sailing stand. I was wearing boat shoes at the time, and the sailing coach there noticed and said, ‘Are you a sailor?’ I said no, and he asked me to take a seat and told me what they could offer. That’s how it kicked off. I went out for the first session, and surprisingly – I even surprised myself – I took to it straight away. I came third in my first ever race.

Sailing is a part of my identity now. Having had a brain injury, and not working anymore, you can lose your identity, and when you get it back, you hold on to it as hard as you can. Sailing gave me that sense of identity back. When you go out, the main question that people will ask is ‘What do you do?’ If you don’t have an answer to that, what can you say? Once, I said I do nothing, and that felt so wrong. Now I can say I’m a sailor.

Working on my book has given me that sense of identity back too. There’s a reading service called Interact [10] which gets actors to read books to hospital patients. One day I was in my bed in hospital, and I saw this very good-looking woman go over to the guy across from me. They didn’t look like a fitting couple, you know? They didn’t match. I was thinking, ‘could that be his sister – maybe his wife?’ I saw her bring out a book and read. Once she was finished she saw me looking, very curious, and asked if I’d like a book to be read to me. That book put a smile on my face, and it’d been a while since I last smiled.

She was coming every week, and we were getting to know each other – she was asking questions about my life, intrigued, and eventually she said, “Have you ever thought about writing a book?” I said “Sure, but I don’t have the means to do that.” She said, “There’s someone who’d be very interested in your story – the manager of the reading service – and you could talk to him about writing your story.” I decided to write a letter to him, and within two weeks he came down to see me. I told him what I wanted to do. He was planning to write a book for the charity itself, but he said that we could write my book and release it in the charity’s name. Every week, him or one of his employees – the girl who read that book to me the first time – would come and interview me. We’re about halfway there now.

The experience built my confidence up. It showed me that sometimes I do underestimate myself. All these goals came from when I was in hospital. As much as it was a traumatic time for me, I’ve actually got really great memories of it. You could say that the good has over-passed the bad.

Even before my accident I knew that anger could not solve anything. Anger eats away at your immune system. So after the accident I wasn’t angry – but I was disappointed that this person, whoever it was, didn’t have a shred of humanity in him, to do something like that: not to stop, not to call an ambulance, to just drive away and live their life. But I wasn’t angry, and I wasn’t depressed. I can say, hand on my heart, I never shed a tear. I’ve been close, but I never cried. If anything, I felt blessed to survive and make the most of it.

I didn’t think like that straight away, or even when I left hospital. It took years. Sometimes I realise I’m not as over it as I thought. I was asked to give a talk at the Stroke Association, to tell my story. What I wasn’t prepared for was how emotional I felt when I was talking – I was overwhelmed. When I feel that emotion inside me, my mind goes to the logical side and I try to analyse it. Interesting one for a psychologist. Go ahead and analyse that!

When I feel it now, it’s not the most raw form of that particular emotion. I think I feel it as little spikes here and there. That’s the best way to describe it – a little spike, it goes back down, a little spike again somewhere. If I didn’t feel like that, I’d be detached.

I’ve told the story so many times, I get comfortable saying it. If it can help someone who’s been in a similar situation and has no calm over that particular event – if it can help them move on – then it’s worth telling all over again.

Sometimes I wonder what I’d say to the person who hit me, if they could hear me talk about it.

Not everything happens for a reason. If I hadn’t had that traumatic accident, where would I be? I couldn’t answer that question. I do know one thing. If that person who hit me asked me to forgive them, I would. I’d have to think about it, but I would.

Something I’ve stopped asking – one of last year’s resolutions – is the question ‘Why?’ So I wouldn’t ask them that. Even though I’d love to ask them that. I wouldn’t even rephrase the question to mean the same thing without saying the word.

Not calling an ambulance, not stopping, just leaving me there in the road.

Maybe if you need an answer to the question ‘Why?’ you can’t fully have forgiven someone – it’s not full-hearted forgiveness.

No, I wouldn’t ask why. To that person, I think I’d explain how I’ve let it go, and I’d ask them – “Do you still think about it?”

Me and time have a love-hate relationship now. It took me a long while to realise that I’m quite slow in how I move now. I give myself time because I don’t want to rush: that’s when mistakes happen – you lose something or you forget something. But even though I take my time, somehow I still find myself rushing at the last minute. Maybe there’s a deeper reason why I’m always racing against time. I’ve always lived in the fast lane – that’s just how I am. Now I’m in the slow lane, and I’m learning a new rhythm.

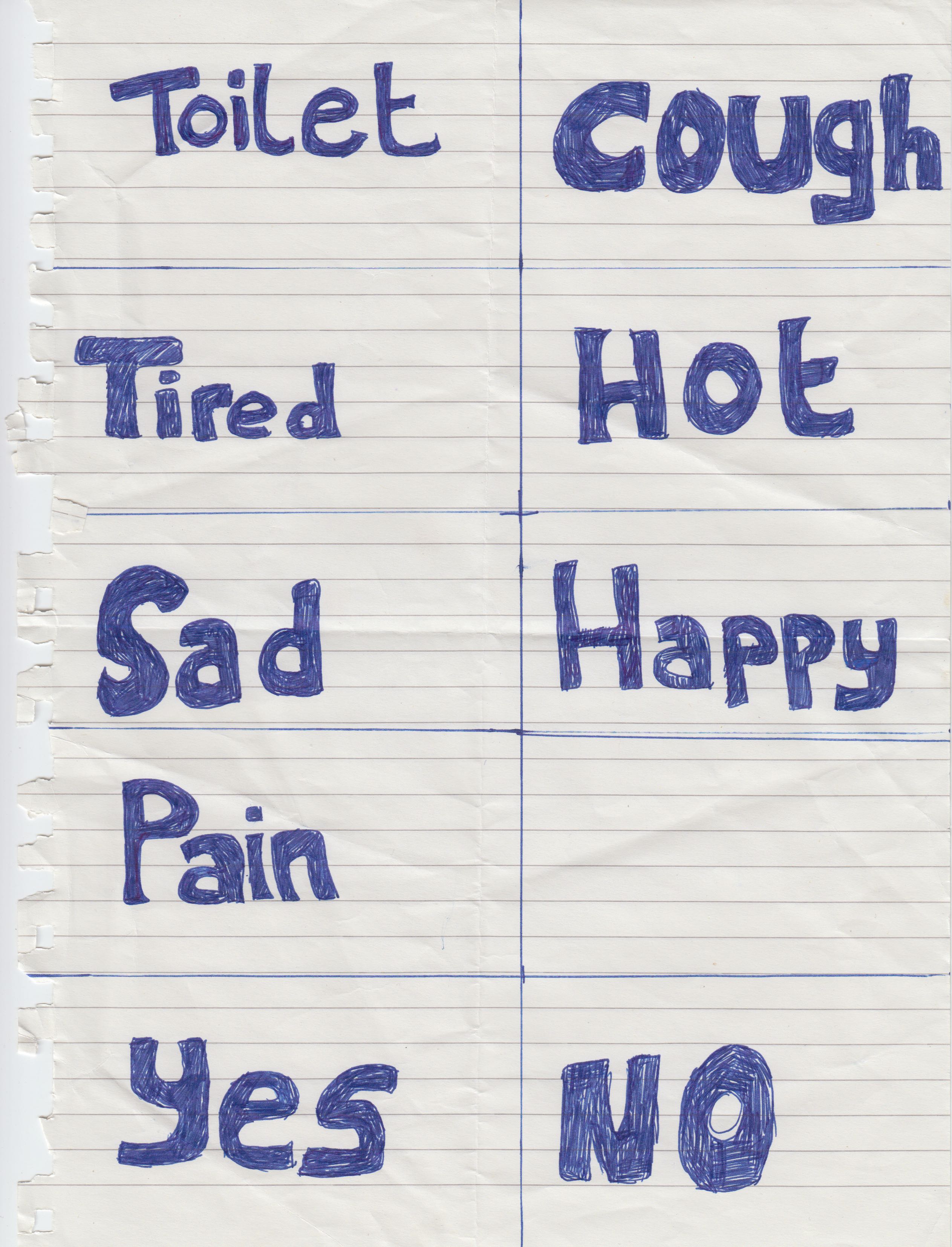

The challenges I face now are about getting back into work. I’ve got neurological weakness in my left hand and foot. My thinking is slower and I get distracted. I start to read, I look away, and the moment I come back to the page I’ve lost my place.

I find it hard to find my way around new environments. At each place I’ve lived since my injury, I’ve needed someone to go out with me while I’m getting used to the area. That’s why I’m trying to move back to Camden – it’s the area I know, and I’m comfortable to move around there. As part of my rehab, the therapist showed me the way to a new place and I had to make the return journey on my own. On the way there, I concentrated on picking out landmarks to help me remember the route. It took a long time but I found my way back.

I want to do more travelling before I settle down. I don’t think it’s out of my system. There are parts of the world I still want to see. I want to see its furthest outskirts.

I suppose I’m hoping that the things I’m doing – the sailing, the book – will eventually open a door back into work. Work comes down to one thing – money. Money comes and goes – I’ve always been a bit blasé about it. With me, it always comes down to the experience.

Rehabilitation Services Discharge Report

17.12.12

Cognitive Function

Assessments indicate that Mr Kabeja experiences difficulties with attention, temporal awareness [11], visual memory, problem-solving and abstract reasoning. Mr Kabeja often has to re-start tasks from the beginning if distracted, and struggled with tasks that required any form of divided attention.

Mr Kabeja has demonstrated good episodic memory, though he continues to have difficulties with route finding. He benefits from an errorless learning approach and lots of repetition to learn a new route to help prevent him from becoming lost. Landmarks have also been useful in helping Mr Kabeja with route planning, as he uses them to identify and remember routes. In the final week of his stay he has agreed to take part in an exercise where he will be taken to a place he does not know and has to use these strategies to find his way back.

My girlfriend and I have been together for a year and a half now. When I was in hospital I was quite worried – what kind of relationship could I hope for now? What kind of girl would have me? I’d met her at a house party years ago, before my injury, and after my accident she got in touch. We got to know each other again on a much deeper level, and we realised we were compatible. She knew all about the injury so I didn’t have to explain everything. I’m still the same as I always was when it come to relationships. I’m just enjoying every little moment more than I was before.

If I heard this story from somebody else, I’d think all those fabricated memories would have destroyed my instinct – but actually, I trust my instinct more. Before my accident I was very cautious. When I made any kind of decision I’d look at all the options and nit-pick at every detail, till I’d find one negative thing and think, ‘that’s not for me.’ Now, if I feel it within me and I feel it’s right, I go for it one hundred percent. Maybe because my memories in my mind fooled me once, I have to find a different way of telling if something’s real or not.

The other positive thing is that I now laugh a lot. I’m always smiling. It’s not like I’m smiling because I want to – I don’t know what’s the right word for it. I get overwhelmed with this feeling of butterflies in my stomach – you know people talk about butterflies in their stomach? It’s not really butterflies. It’s an increase in dopamine [12], but we’ve renamed it butterflies. I’ve got an involuntary smile. It just comes to me. I could be having a serious discussion and all of a sudden, I smile. I feel that flood of dopamine hit me.

At college we learnt about the chemicals your body produces and how that affects you – how they can structure your mind, your appearance, your character. It’s all to do with chemistry: take pheromones – people can be attracted to their partner’s smell. A smell can open up your eyes. I had an interest in that beforehand, and of course even more so since the injury. We don’t understand how the brain works. I don’t think we fully understand ourselves.

I smile and laugh so much now that my mum says, “Hey, is that to do with your brain-injury?” That just makes me laugh even more. I suppose at the early stages she was getting worried about it, but now she thinks, ‘At least he’s happy.’

I’ve had those thoughts too – what’s me, and what’s just how my brain was affected? Is that my brain-injury or is it me? I just go with it now. If anyone has a problem with it, and they ask me, I’ll let them know. Until then I’ll just go with it.

The way I’d describe it is: I’m Alpha 2.0. The experience of having this brain injury has taught me so much about my own body, things I’d never have learnt throughout my life unless something traumatic like that had happened. It’s a new version of me, and a better version, because I’ve learnt so much.

© Alpha Kabeja / Headway East London (2016). All rights reserved

Subdural haemorrhage (SDH): a collection of blood between the dura mater and arachnoid membranes surrounding the brain. This can result from a torn vessel and is common in traumatic brain injury. The primary concern is the increased intracranial pressure the bleeding causes – which can lead to displacement and crushing of brain tissue.

Midline shift: the displacement of the brain inside the skull, with portions of brain crossing over the centre line from one side. Midline shift is diagnosed through scans such as Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Images (MRI) and is a common consequence of subdural haemorrhage.

Craniotomy: removal of a section of bone from the skull to allow for brain surgery or, in case of haemorrhage or trauma, to allow the brain to swell without being crushed.

Evacuation of blood clot: the surgical removal of blood resulting from the haemorrhage.

Intracranial bolt: also known as a ‘subdural screw’, this device is inserted into the cranial space through the skull and membranes surrounding the brain in order to monitor pressure inside the skull.

Bone flap replacement: surgery to replace the bone removed in craniotomy.

Raised intracranial pressure (ICP): increased pressure inside the skull caused by internal bleeding. This is a primary mechanism of injury in head trauma (see note 1).

Frontal lobectomy: removal of part or all of the frontal lobe of the brain. Lobectomy is performed where brain tissue has been damaged and/or where it is the site of ongoing disease, e.g. seizure or bleeding, that may cause further damage to surrounding tissue.

Confabulated false memories: confabulation refers to the presence of memories that cannot be verified by external events. Confabulations have a distinctive feeling to the person – distinct from dreams or hallucinations, they feel like real memories even where the person understands that they are false. Sometimes confabulations can be fantastical or unlikely in their content but they are often related to the person’s hopes or fears. See also the Who Are You Now story ‘Matthew’ from 2015.

Interact Stroke Support: a charity offering live readings for stroke survivors in hospital and in the community. For more information see Interact’s website.

Temporal awareness: sense of time passing. Some brain injury survivors experience alterations in their perception of time.

Dopamine: an organic chemical with several complex roles in plant and animal bodies. In animal kidneys it influences urine production; in the blood vessels it influences vessel dilation; in the pancreas it reduces insulin production; in the brain it acts as one of several known neurotransmitters – carrying messages between nerve cells. It is thought to have a role in reward-motivated behaviour, control of movement and in the release of hormones.